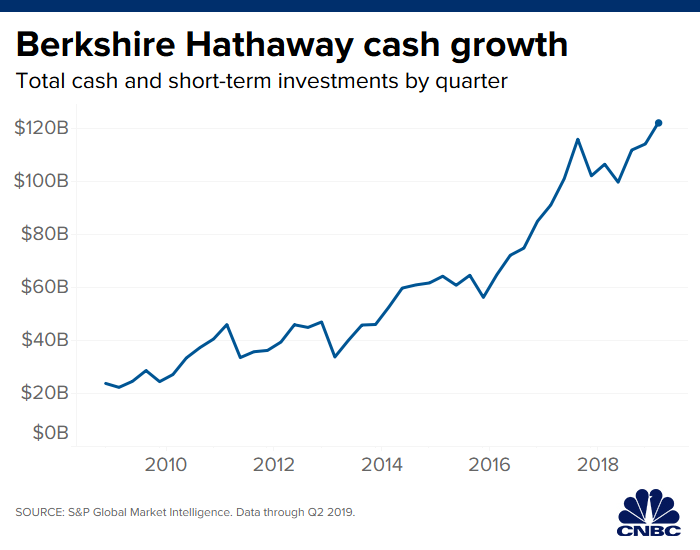

Berkshire Hathaway's cash and short-term investments on the balance sheet have grown from roughly $24 billion ten years ago to near-$123 billion as Warren Buffett's conglomerate gets set to release its latest earnings on Saturday morning.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Earlier this week California Governor Gavin Newsom pulled the utility sector equivalent of Financial Crisis bailout pleas: with wildfire-bankrupted PG&E facing widespread outrage for its power shutdowns in the face of another fire season in California, Newsom practically begged Warren Buffett to buy the utility.

Buffett made some shrewd moves during the worst of the financial crash and its aftermath to shore up confidence in companies including Goldman Sachs, General Electric and Bank of America, but the Berkshire Hathaway chairman and founder has previously denied any plans to make a bid for PG&E (rumors have been swirling since the PG&E crisis began that the distressed utility could be a Buffett's acquisition target). But PG&E does not exactly have the backstop of the U.S. government that the largest banks had, and PG&E is not just a distressed asset.

No matter what it says about the reasons for its bankruptcy as a means to manage wildfire claims, the utility is going through an existential crisis with no clear way out — some say the state needs to step in and take over the company, or that a single, large utility will no longer be able to exist in the wildfire future of Northern California.

Buffett's own existential crisis, in an era when beating the index fund gets harder and harder, is what master dealmarket Buffett's company Berkshire Hathaway symbolizes if it can't find ways to spend the cash that is piling up on the balance sheet in a way that increases return to shareholders. In 2009, Berkshire had roughly $23 billion in cash. Since then, the company has added over $100 billion in cash and short-term investments, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data through the second quarter. Berkshire's third quarter 2019 earnings on Saturday morning showed its cash pile growing to $128 billion. Buffett's company is currently on pace for its worst annual stock performance since 2009.

"He pinned himself into a corner a few years ago, saying I can't have $150 billion in cash in three to four years and say that's alright," said Greggory Warren, a Morningstar analyst who covers Berkshire Hathaway.

Underperformance versus the index, deals that have not worked out well, such as Kraft Heinz (thought it showed signs of life in its most recent earnings), and increasing willingness on Buffett's part to consider share buybacks, all point to the the importance of moving that cash into investments that generate a return.

Berkshire Hathaway's edge has always been about generating huge amounts of cash from its insurance operations and finding ways to generate higher returns on that cash, either through acquisitions or into capital-intensive businesses, such as the utilities it owns. Berkshire Hathaway Energy is a huge utility market player in the U.S. serving more than 10 million customers, as well as controlling transmission infrastructure and renewable energy projects across many states.

The lack of big deals — or as Buffett has referred to them in recent years, the "elephant gun" hunting — has started to have consequences among shareholder. A long-time Berkshire Hathaway holder and fund manager, David Rolfe of Wedgewood Investments, recently sold his entire stake in Berkshire. While a relatively small stake, Rolfe's concerns do get to the heart of the cash matter, and he turned Buffett's own words on him in a letter to clients discussing his decision, saying Buffett was "thumbsucking."

CNBC Evolve will return, this time to Los Angeles, on Nov. 19. Visit cnbcevents.com/evolve to apply to attend.

"Their utilities business (Berkshire Energy) needs continued acquisitions to restart utility growth," Rolfe wrote. Of the cash hoard he wrote, "Rather than our previous hard expectation of a valuable call option on opportunity in the hands of one of the most elite capital allocators extant. Further, the efficacy of putting this cash pile to work (plus +$25 billion in annual operating cash flows in Omaha) will be paramount if Berkshire Hathaway is to once again regain their former status as a meaningful grower over just baseline U.S. GDP growth."

Morningstar's Warren said he would have preferred to see a more regular run rate of share repurchases and it could be done without impacting the "dry powder" for acquisitions.

Other analysts, even ones skeptical of Berkshire's future growth prospects, are more patient on the share repurchase strategy: "To the extent that Berkshire isn't leveraging its massive cash hoard and 'overpaying' to buy back its stock, that seems like a good thing (although the benefits will hopefully only emerge in the long-term)," said Meyer Shields, KBW analyst.

If the market doesn't turn, a couple of years out he will be sitting on $150 billion.

Greggory Warren

Morningstar financial services analyst

Time is running out for Buffett to wait on a market downturn as a buying opportunity.

"If the market doesn't turn, a couple of years out he will be sitting on $150 billion. The company is already kicking off $20 billion in free cash flow a year," Warren said.

The situation leads Warren to conclude a utility acquisition is among the right deals for Buffet to pursue.

"Ideally, what they need is another utility acquisition. You can only build out so much within your own territories before they are saturated."

Berkshire has been able to plow money into renewable energy projects over the past decade. Berkshire Energy has invested $6.5 billion in solar and its MidAmerican Energy affiliate in the Midwest is the largest producer of wind energy in the U.S. But the tax credits that Berkshire can claim on renewable energy projects are winding down in the next few years, making those deals less lucrative to make after the immediate-term future. "There's not going to be as much money thrown from capex on that side," Warren said. "Some of the wind stuff they put in needs upgrades so they can put some money to work there, but new projects may not be as big."

Buffett has tried to swoop in and buy distressed utilities. And been outbid. In August 2017, bankrupt Texas utility Energy Future Holdings abandoned a deal to sell power transmission company Oncor to Berkshire for $9 billion when Sempra Energy offered a higher price, "a rare blow for Buffett" who avoids bidding wars for companies.

"10 to 20 years from now there will only be a handful of big utilities in America and Berkshire will be one of them, but right now it is cost prohibitive," Warren said. "Yield income-based investments flooded into utilities in the past 10 years, but at some point we have crumbling infrastructure, or people just don't have access. Or debt levels are too high. It will take someone with deeper pockets," Warren said. "If you can by infrastructure assets and put the money to work in them, and get favorable rates from the state [utility commissions], it is worth doing."

Utility stock peak

That movement by yield-seeking investors into utility stocks which Warren referenced points to one of the challenges for cost-conscious Buffett: Utility stocks are trading at all-time high levels.

"The industry has been doing reasonably well, but the stocks are doing even better," said Steve Fleishman, Wolfe Research managing director and utilities industry senior analyst. "The biggest issue is valuation."

Utilities on average are trading at 20 times forward earnings, which is not just an all-time high but a premium to the S&P 500.

Fleishman said there has been a lot of mergers and acquisitions activity, but it has been small companies bought at large premiums, though with one deal feature that is not a problem for Buffett: "Lots of cash deals."

The landscape for utility deals could improve for Buffett, the Wolfe Research analyst said, because M&A has slowed as buyers' balance sheets weakened — predominantly private equity buyers, foreign utilities coming in, and some infrastructure funds.

"Overall, it's still expensive, however, it is an area where you can put a lot of capital to work upfront and what Berkshire always liked about utilities is you keep putting money to work, the more you can keep investing over time you can earn a good return," Fleishman said. But he added that given the valuations, "It's hard to find entry points they would like."

Even the valuation gap between the best and worst in the sector is limited as an M&A advantage.

"The low risk, high quality names just keep going up in valuation," Fleishman said. That's led to a feedback loop in which public market investors just keeping buy the better names. "It has not paid to take risk as a utility investor. Valuation has not hit a ceiling so why bother owning the riskier ones? That won't last forever but that's the mindset now," he said. Meanwhile the weaker names are "trading cheaper to a group that is not cheap overall."

PG&E may be the biggest risk of all in the utility space, and there's reason to stay away. Fleishman stressed that Buffett has publicly denied any interest in PG&E in the past, but did say given Berkshire Energy's strength in the Western U.S., "geographically it makes sense."

But that is not enough. "The operating risks are high and I would say hesitate to open deep pockets to risks in California right now. That's an extreme case," the Wolfe Research analyst said.

There are other discounted names, more diversified companies not trading as well, but that is mostly in the unregulated power markets, where midstream companies are trading at big discounts to the regulated pure plays, and there are companies that have large pipeline projects at risk of not being finished. "I'm still not sure any of them are cheap enough for Berkshire," Fleishman said. "Their history is waiting until things are cheap so I guess I would be surprised if they bought a utility in the current environment other than a special situation, distressed or overly discounted."

Future M&A challenges

There is more consolidation to come, said Ted Walker, a managing director at Guidehouse's energy consulting firm Navigant. But he said the total size of the M&A pool in the U.S. is getting smaller.

"We are still extremely fragmented," Walker said.

The wave of deregulation and rules that allowed consolidation over the past two decades has only compressed the sector by about 50%, he said. The biggest utilities in the country serve roughly 10 million customers, Berkshire Energy among them.

"From a pure market view there is absolutely room for M&A," he said, and most acquirers are taking the Buffett approach of building a portfolio of companies to gain synergies, and deal with the patchwork of regulations that vary by state. But Walker said that there is less of a correlation between customer base and cost synergies the larger an organization gets. "In our experience, there are not significant economies of scale for a utility that has ten times more customers, on a per customer basis, per mile. It is not more efficient."

In Europe, a utility consolidation wave that would result in a firm covering the equivalent of 20 U.S. state markets is possible, but not in the U.S.

"We are looking at a few deals a year," he said. "I think are some interesting plays in the traditional utility space, but nothing is easy, no low-hanging fruit."

As Navigant looks out at the next five to 15 years, centralized generation seems fairly low return and the opportunities to spend capex on distribution and ultimately receive higher rates from customers is limited. The past decade has been dominated by the regulated utilities and their investments. Walker said in the next five years with efforts to make grids more resilient among areas of focus, there are capital investments to be made, but that has a limited time frame because at some point continuing to make the case to the regulator and customer that spending billions in capital and driving up rates is a value proposition becomes more difficult. "Lots of utilities say the next five years is good, but after that, not sure."

The nascent investment opportunities — the underinvested ones — are in the smart grid, cybersecurity, and being a source for the electrification of transportation. "A third of carbon is transport. It is unnatural for a utility, but it can be done," Walker said.

If we're talking tens of billions of dollars, you have to look at some of the big guys and we have lots of cautionary tales.

Ted Walker

managing director at energy consulting firm Navigant

An even bigger, emerging investment trend is movement to a business model that views energy as a service offering, based on the cloud computing solutions now dominating so many industry evolutions. The private equity money is chasing that opportunity and that is a threat to the traditional utility model.

"We're seeing lots of PE money, single-digit billions building platforms ... energy clouds, future energy delivery platforms ... it could be focused on smart cities," Walker said. Private equity companies are creating a platform of start-up companies to package these services the same way a Salesforce.com offers a package of software services to companies across industries, and that could include a rethink of what a utility does and new models emerging that allow them to provide electrification solutions to corporate fleets, as one example.

"Long-term, stitching together a next generation platform makes more sense and that can cannibalize a utility and lots of smart money is going there."

Berkshire needs to make those investments if it wants to avoid the fate of slow-moving utilities.

"The energy landscape will be massively disrupted over the next decade or two," Walker said. "I am not in the capital allocation business and if I was, I would be looking hard into these spaces as long-term plays. There are lots of economies of scale and disruption that will happen, and new opportunities to build new platforms transcending the traditional model."

He said even though many skeptics have kept saying the level of utility investment has to slow down for some reason, the transition to new technologies like renewables and battery storage, and a more modern distribution grid and better customer systems, continue to provide new investment opportunities.

But even if those investments are a must, they still leave Berkshire with the same big problem: The single-digit billion-dollar investments in the transformation of the sector are not going to move the needle for Buffett.

"If we're talking tens of billions of dollars, you have to look at some of the big guys and we have lots of cautionary tales," Walker said.

This story has been updated to include the cash on balance sheet reported by Berkshire Hathaway in Saturday morning's third-quarter earnings.

Business - Latest - Google News

November 02, 2019 at 12:41AM

https://ift.tt/2PBiDM3

$128 billion and growing: Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway cash puzzle - CNBC

Business - Latest - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Rx7A4Y

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "$128 billion and growing: Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway cash puzzle - CNBC"

Post a Comment